Most of the polyphonic music that survives from medieval England is preserved in manuscript fragments. Magdalen College is one of the few small research libraries to preserve an exceptional collection of such fragments, dating from middle of the fourteenth to the middle of the fifteenth centuries, and testifying to the developments in musical style, as well as in music books production.

Changes in musical style, and musical notation, took place more frequently than for most other written texts, particularly in the case of polyphonic music – and especially at high-level institutions for music-making, such as the English Chapel Royal. Even a beautifully-decorated, complex and rich choirbook, transmitting the latest styles of composition, may have become obsolete, outdated and unusable as early as a few decades after its compilation, thus turning into a possible source for scrap material.

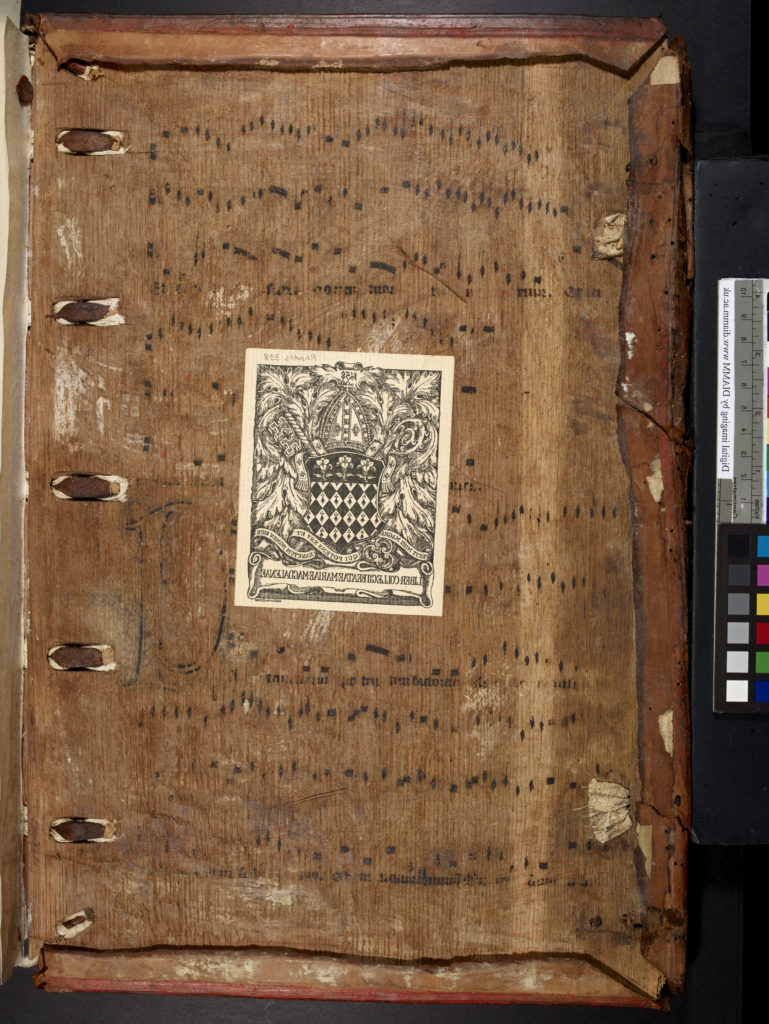

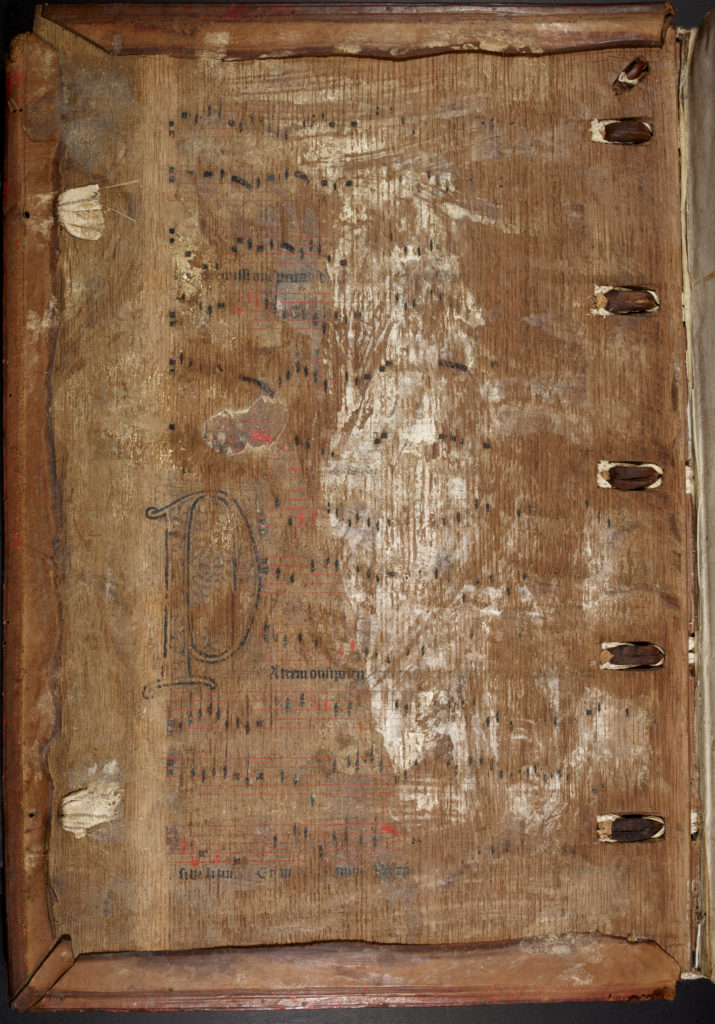

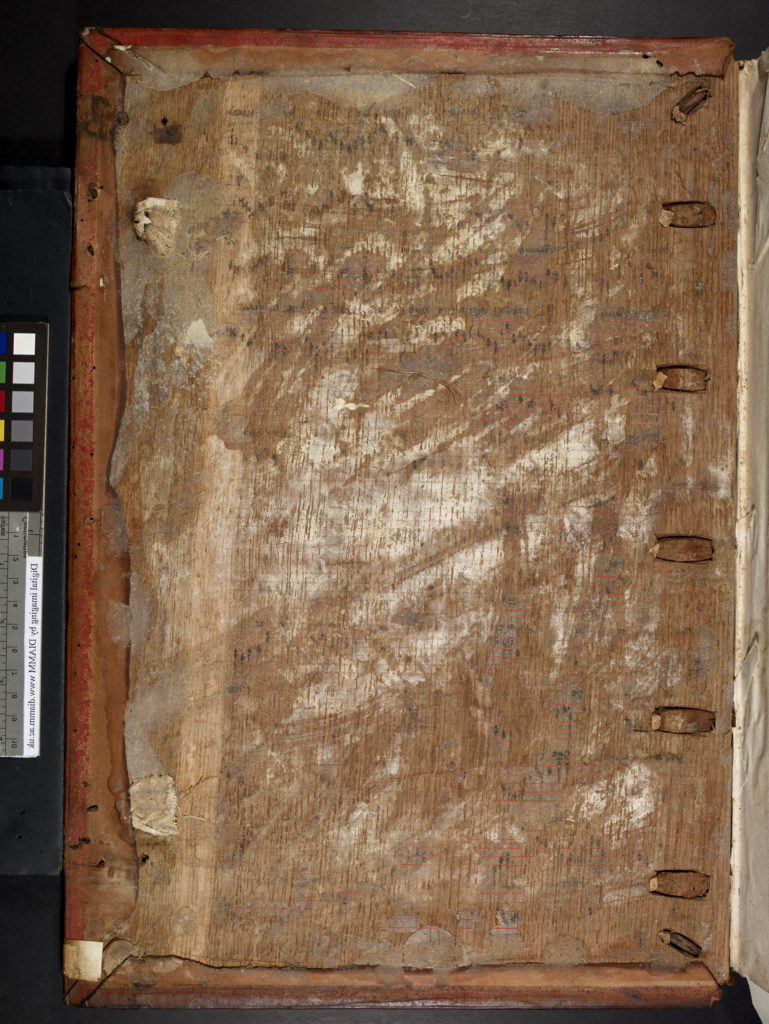

One of the most famous groups of fragments of medieval English sacred music is the one associated to Worcester Cathedral. The Worcester Psalter (background image), an early 13th century Psalter, produced and decorated at the Benedictine Priory in Worcester, survives in a 15th century binding which carried six leaves containing polyphonic compositions that were placed inside the front and rear boards when this book was rebound, 200 years after it was first made. The volume is composed of a calendar associated with the use of the Worcester Priory, later Worcester Cathedral; the Psalms; a set of eleven canticles; a litany with prayers; and the Office of the Dead. It is beautifully illuminated–with work tied to the Glazier Psalter–and features original silk ‘curtains’ to protect a number of the miniatures, some of which have been lost due to historical vandalising. The manuscript is bound between oaken boards that are covered with red-stained leather.

The original book of music from which the endleaves for the 15th century binding came from was a collection of 13th and 14th century polyphonic music. This book was broken up, possibly by the binder Richard Bromesgrove, who was active in Worcester at the time, and then used to pack the new binding around this Psalter. The leaves in Magdalen’s Worcester Psalter were extracted in the early 20th century and returned to Worcester Cathedral; however, the trace of their presence is still visible after five centuries inside the binding.

MS Lat. 100

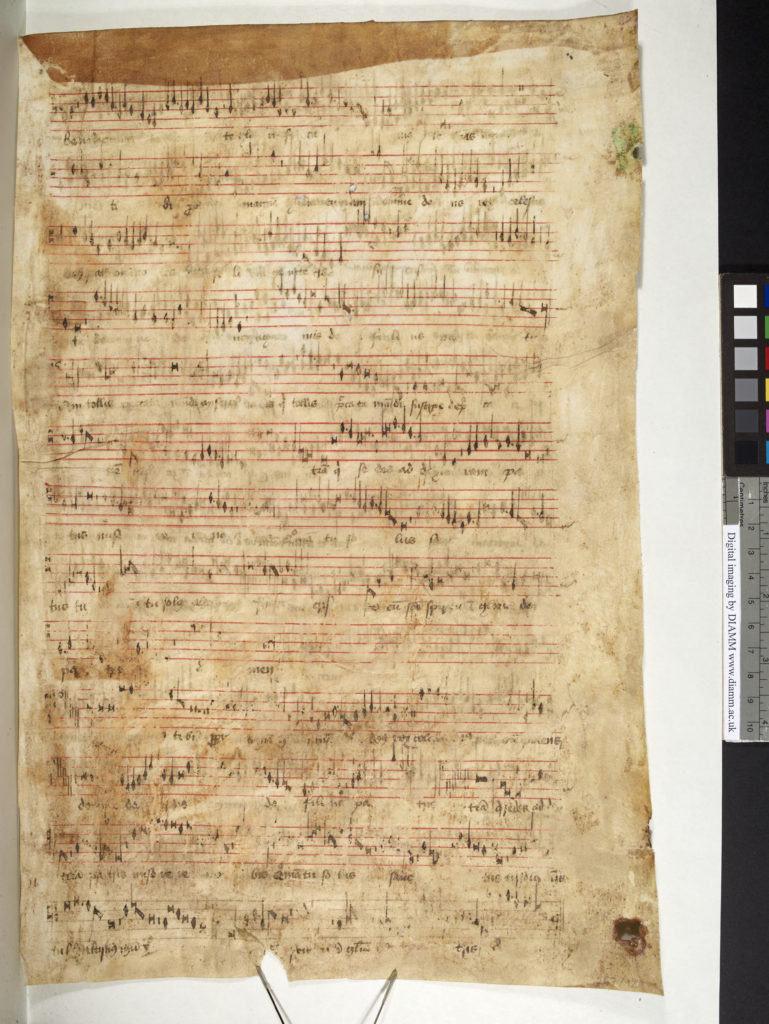

These six sheets (12 pages) of music date from the 13th and 14th centuries formed part of a larger single collection of music composed and assembled at Worcester, commonly referred to as the Worcester ‘Conductus Book’. Originally a collection of over 25 short pieces, the book contained a variety of musical forms from the broad period, including the conductus and the motet. The ‘Conductus Book’ was broken up and used as binder’s waste in the mid-15th century and leaves from this manuscript have been identified as supports for several books, including Magdalen’s Worcester Psalter (MS Lat 100) and books from the Bodleian Library’s collection.

When the Worcester Fragments were removed from the binding of Magdalen MS Lat 100, “ghosts” of the waste left traces of their former existence via transfer onto the 15th century boards and first and last leaves of the Worcester Psalter.

In the early 20th century, Fellow Library Godfrey Driver returned Magdalen’s six leaves of music to Worcester, where they were joined by other related fragments removed from other book bindings and now form part of Worcester Cathedral Library MS. Add. 68. It was not possible to reconstruct the complete original music book from the extant fragments, but enough survived to support performances of a number of pieces, now known as the ‘Worcester Fragments’.

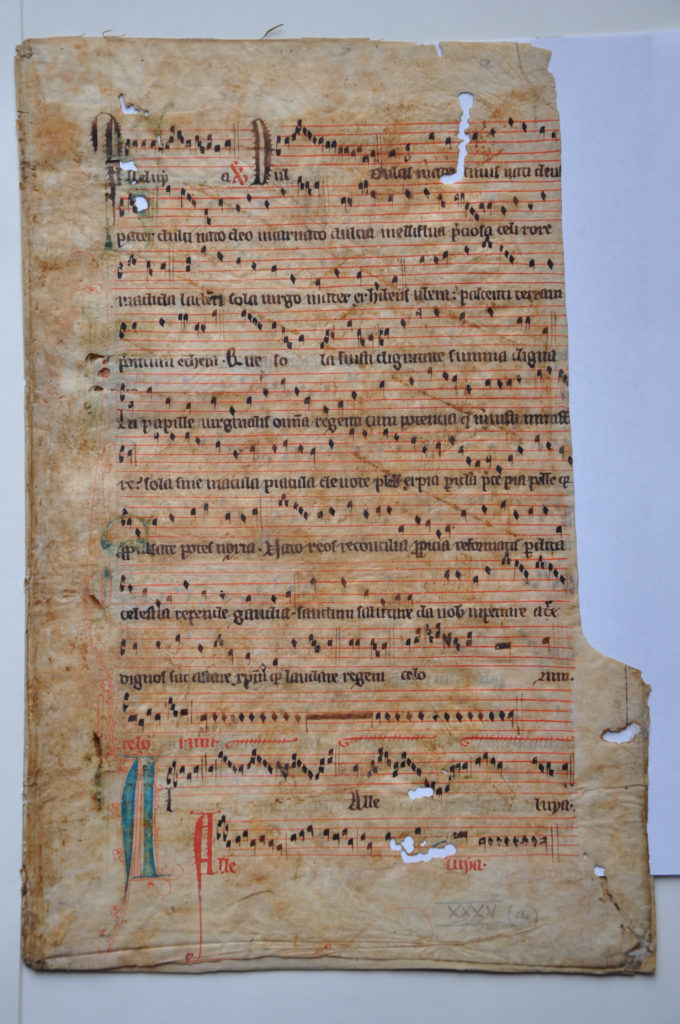

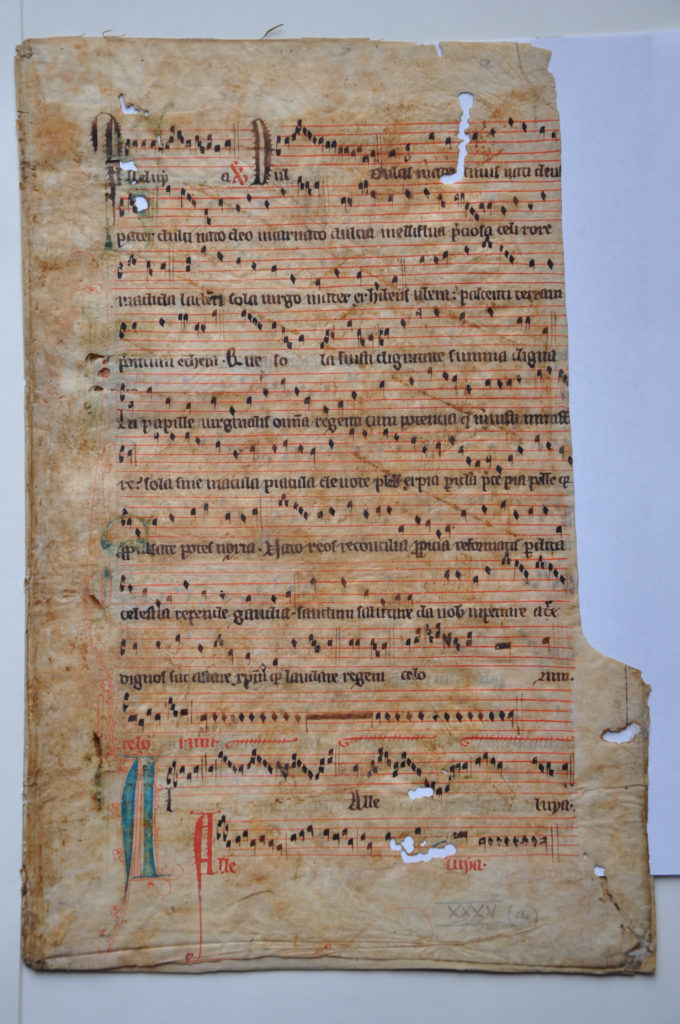

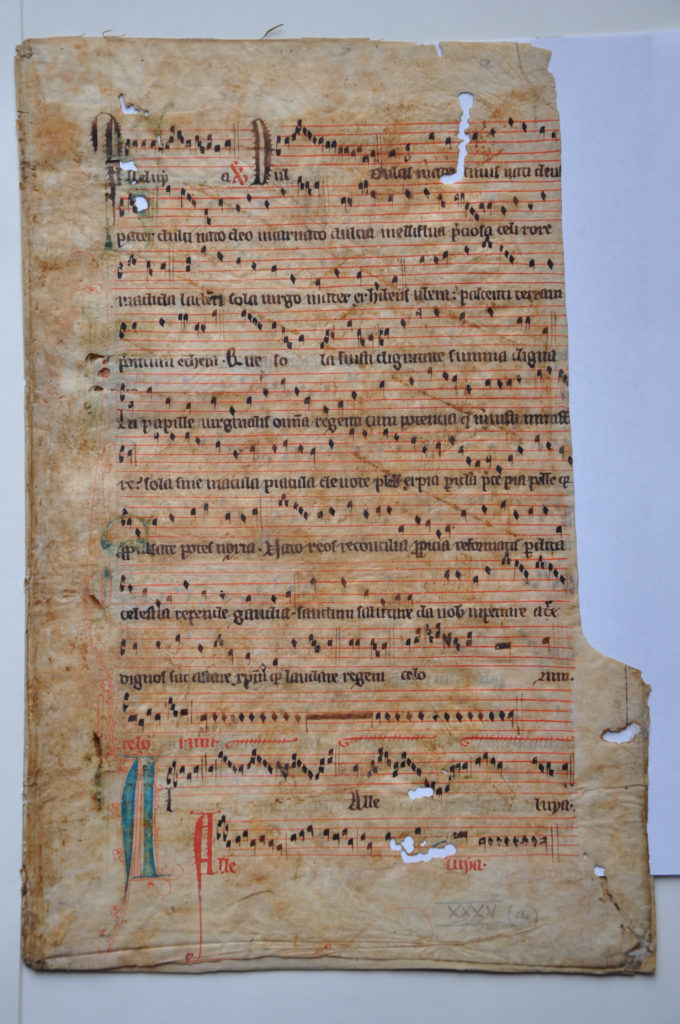

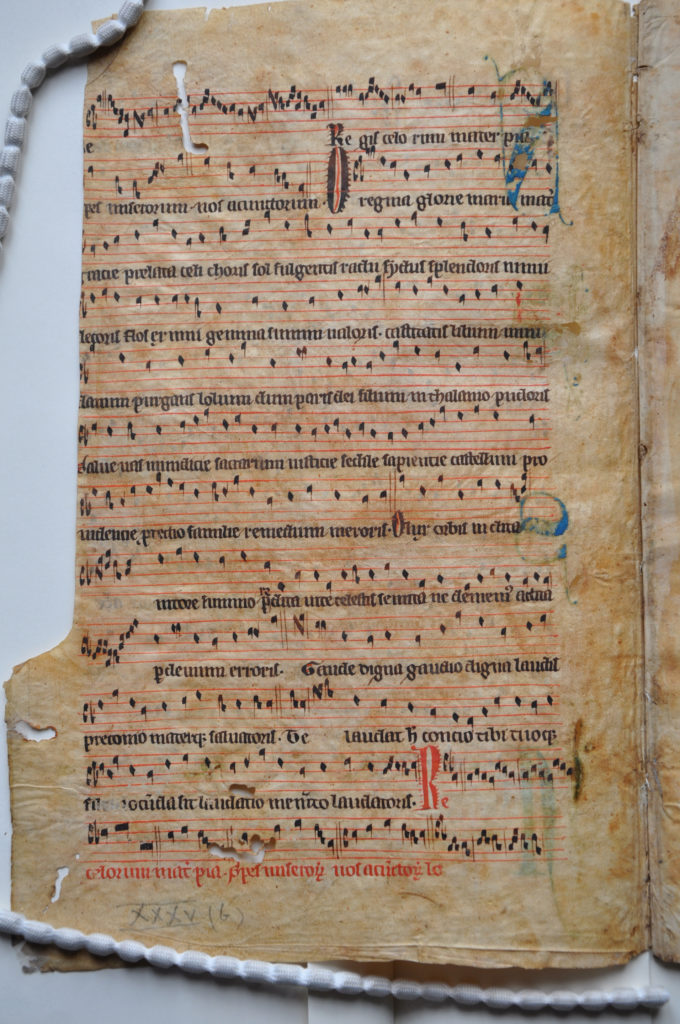

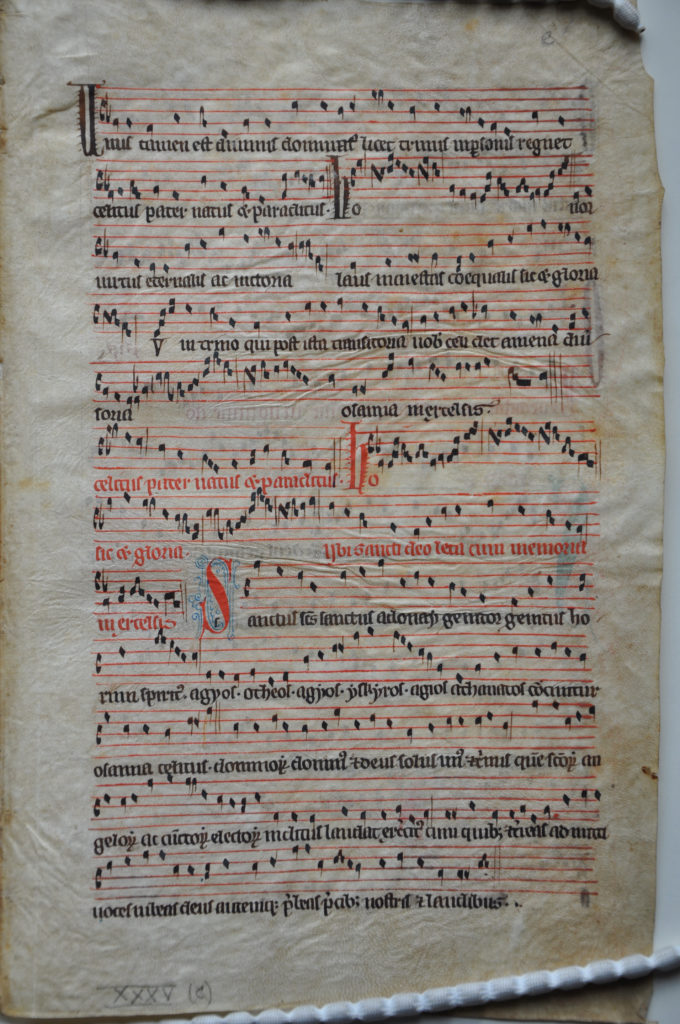

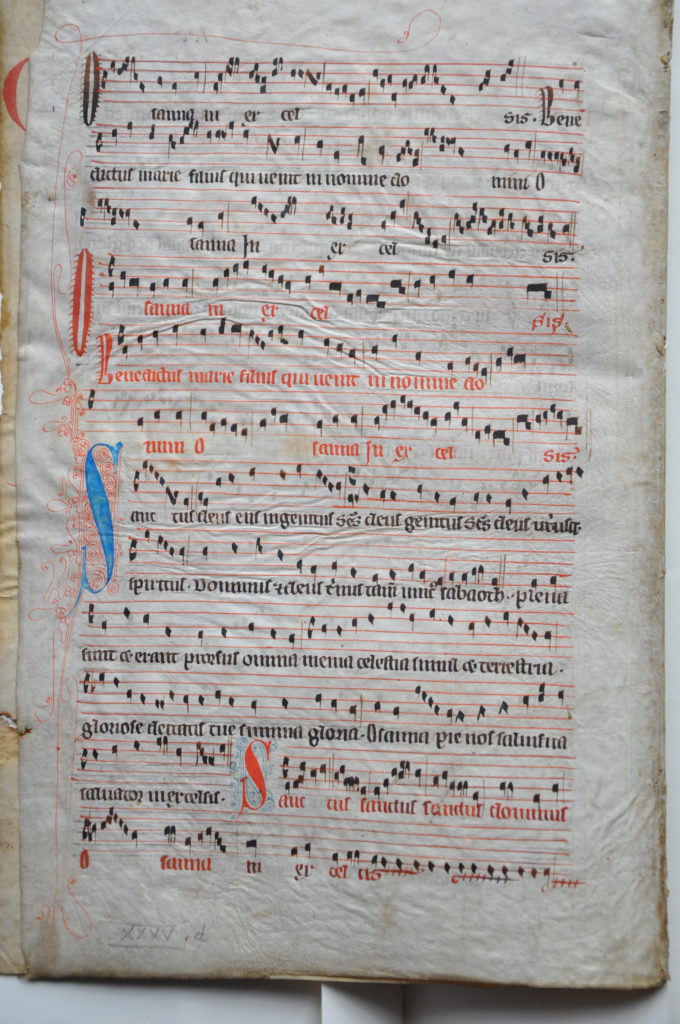

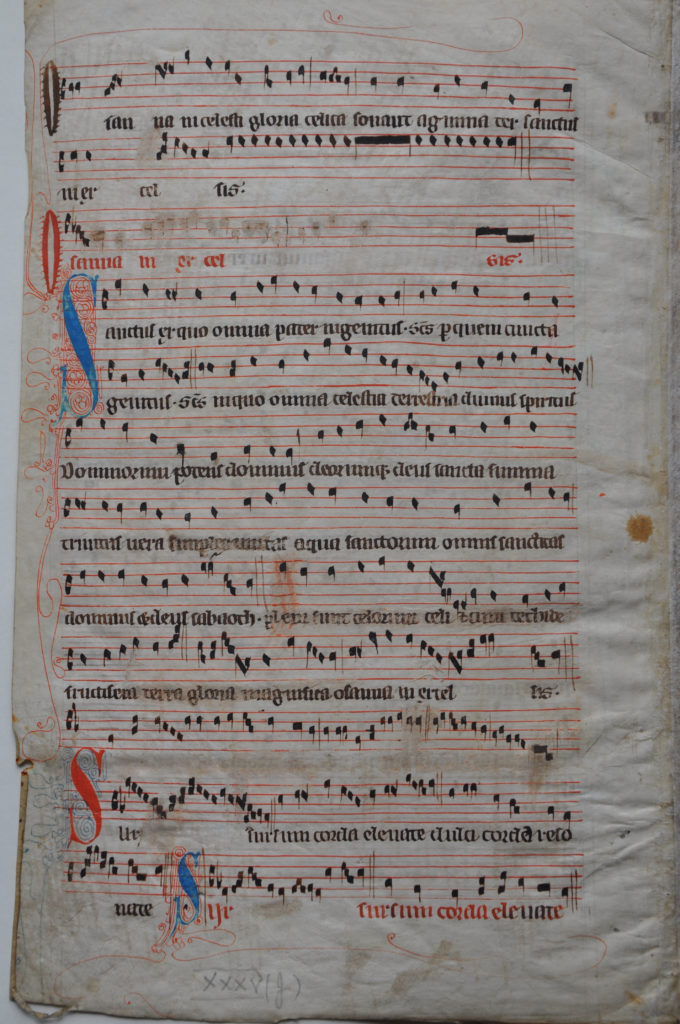

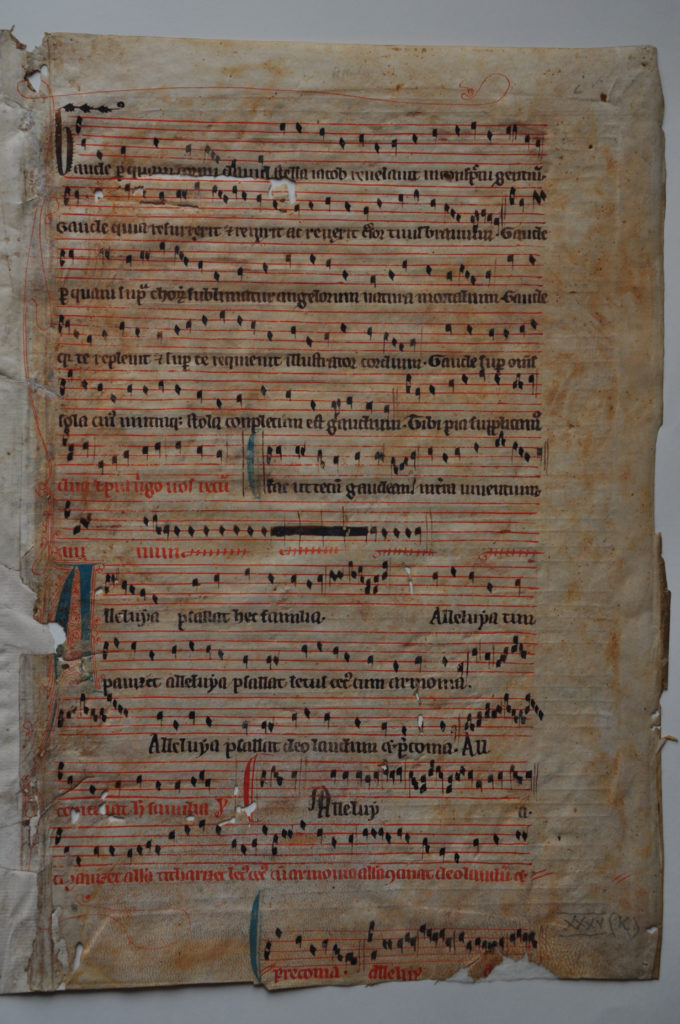

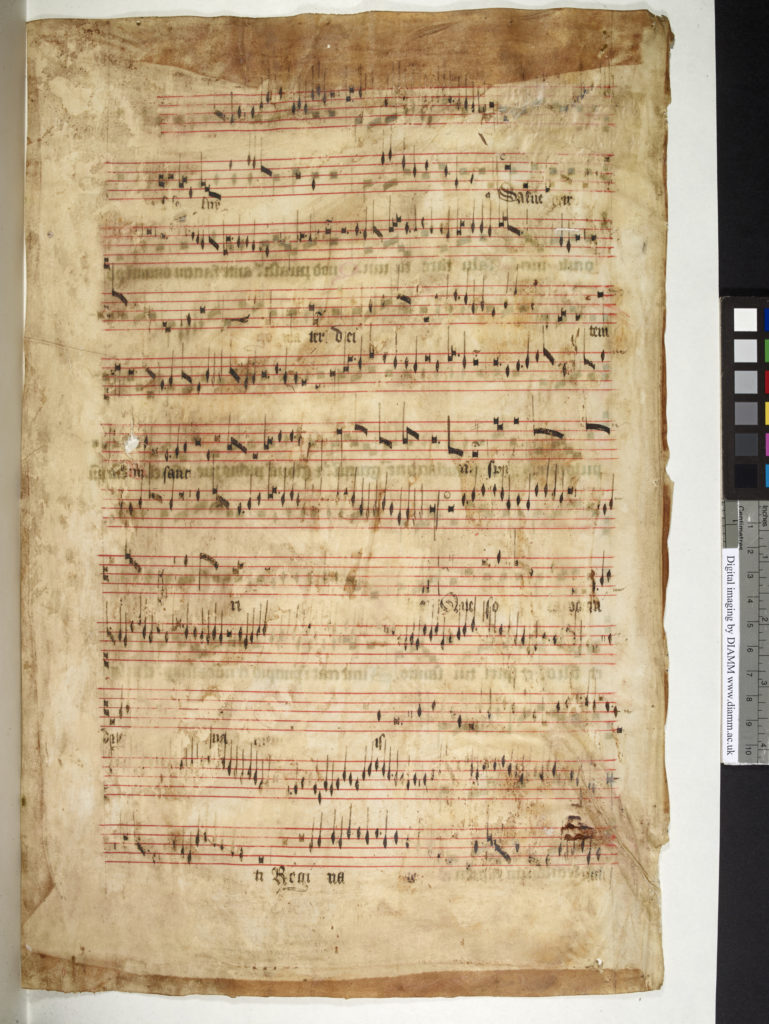

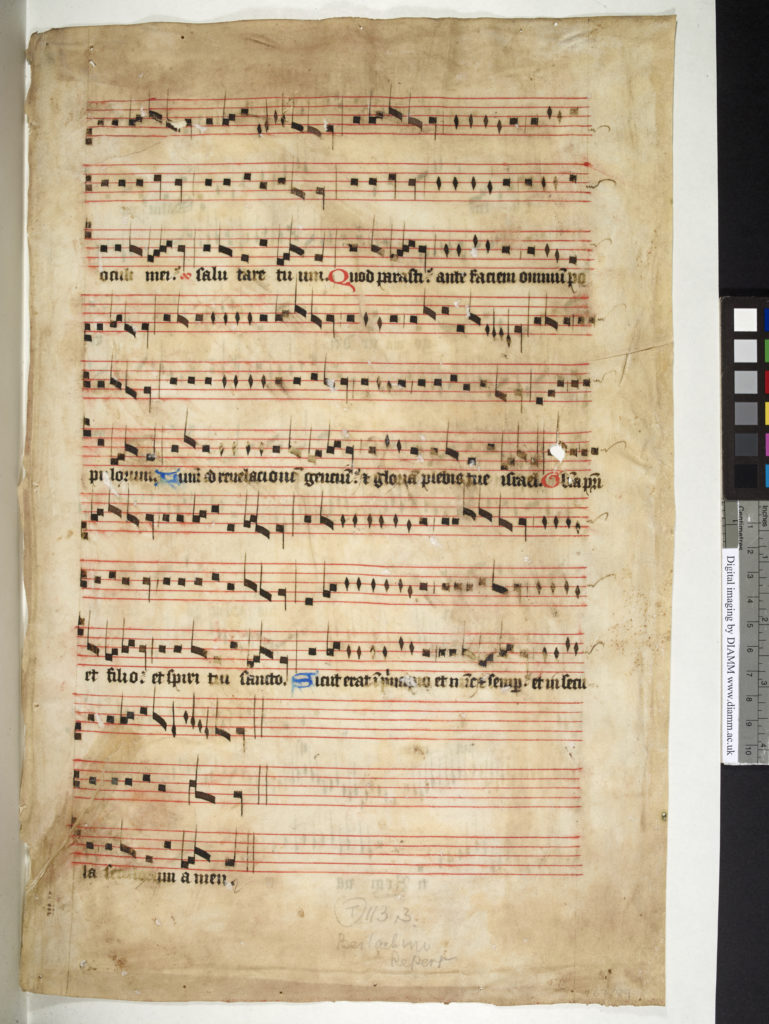

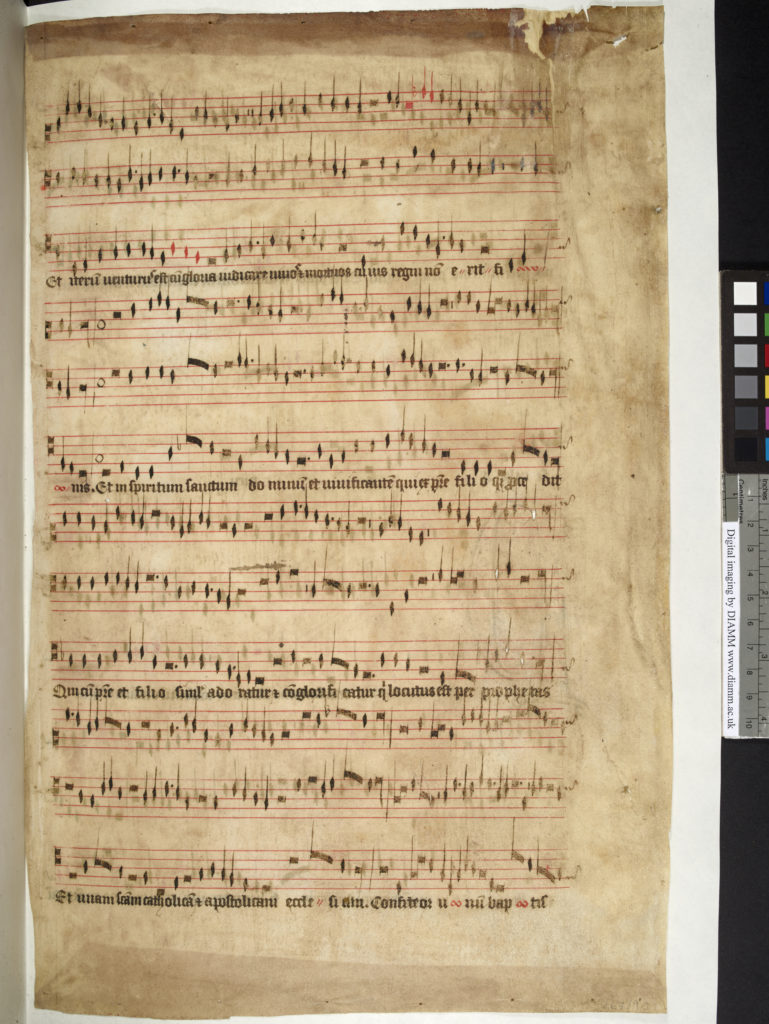

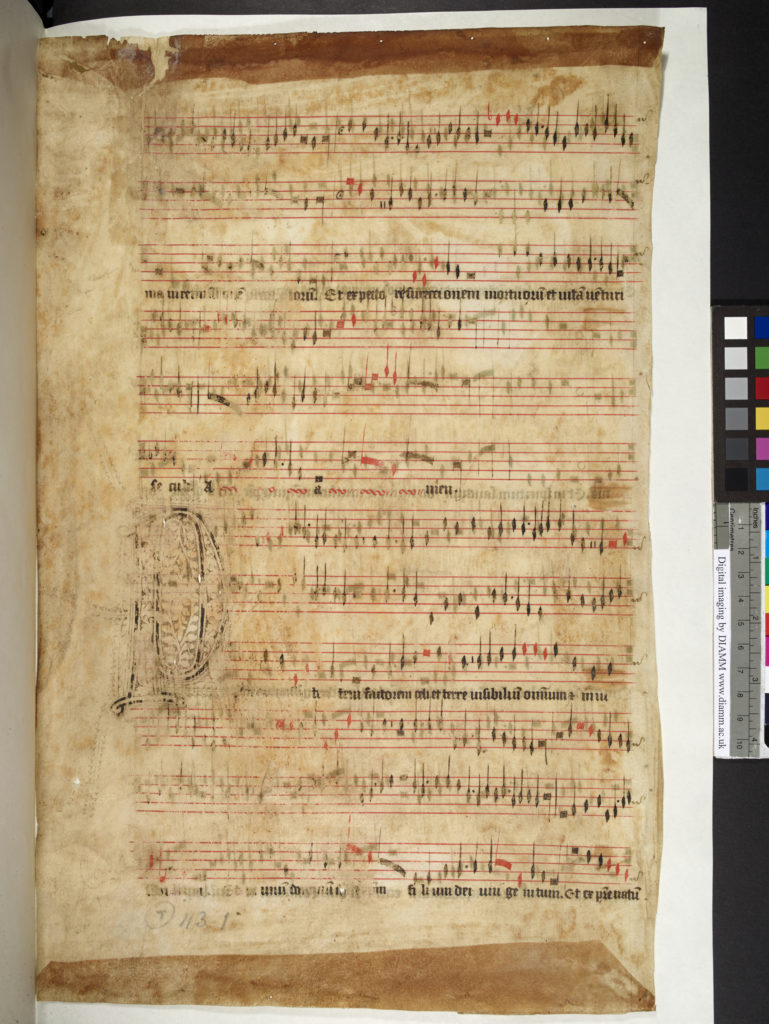

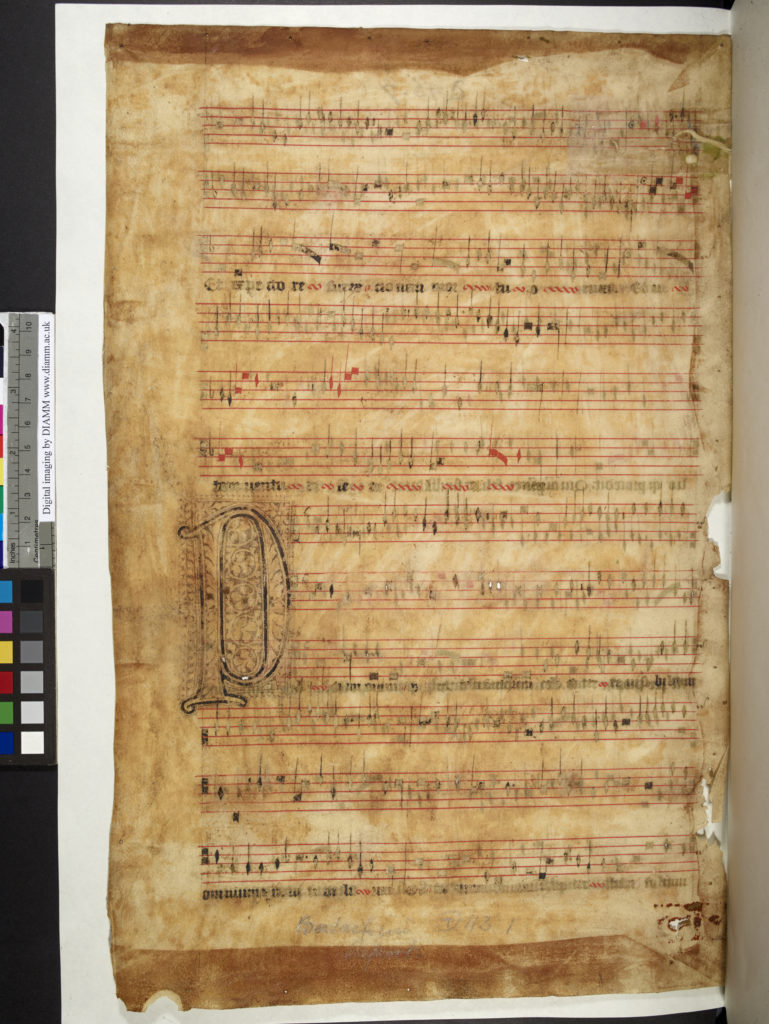

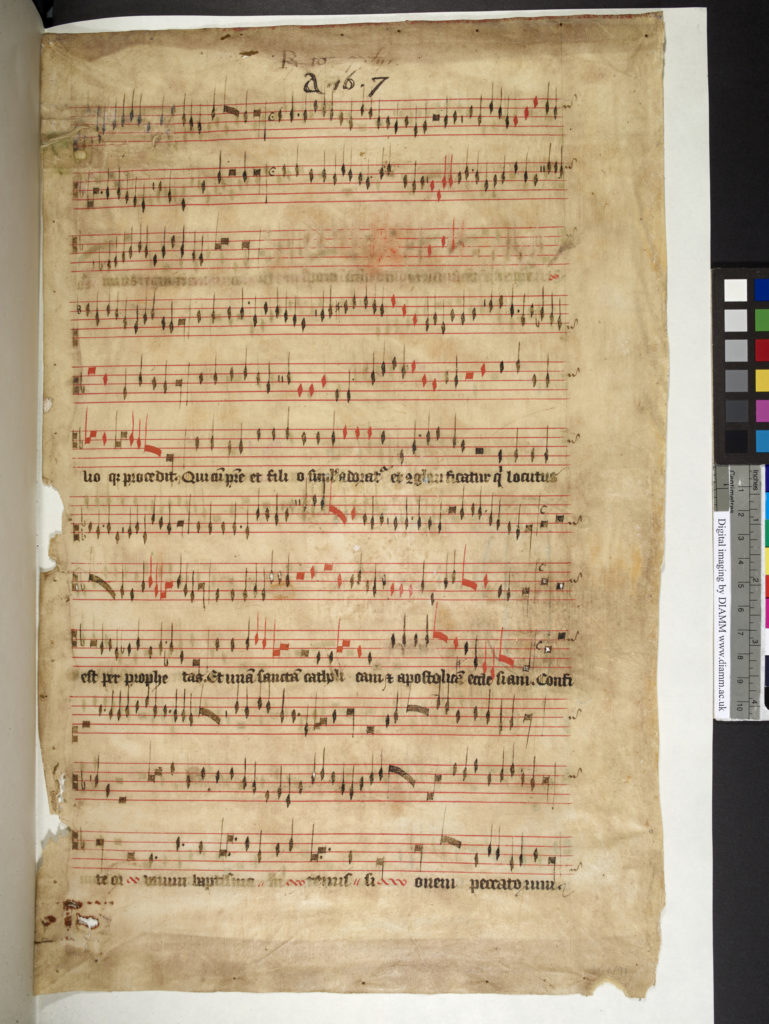

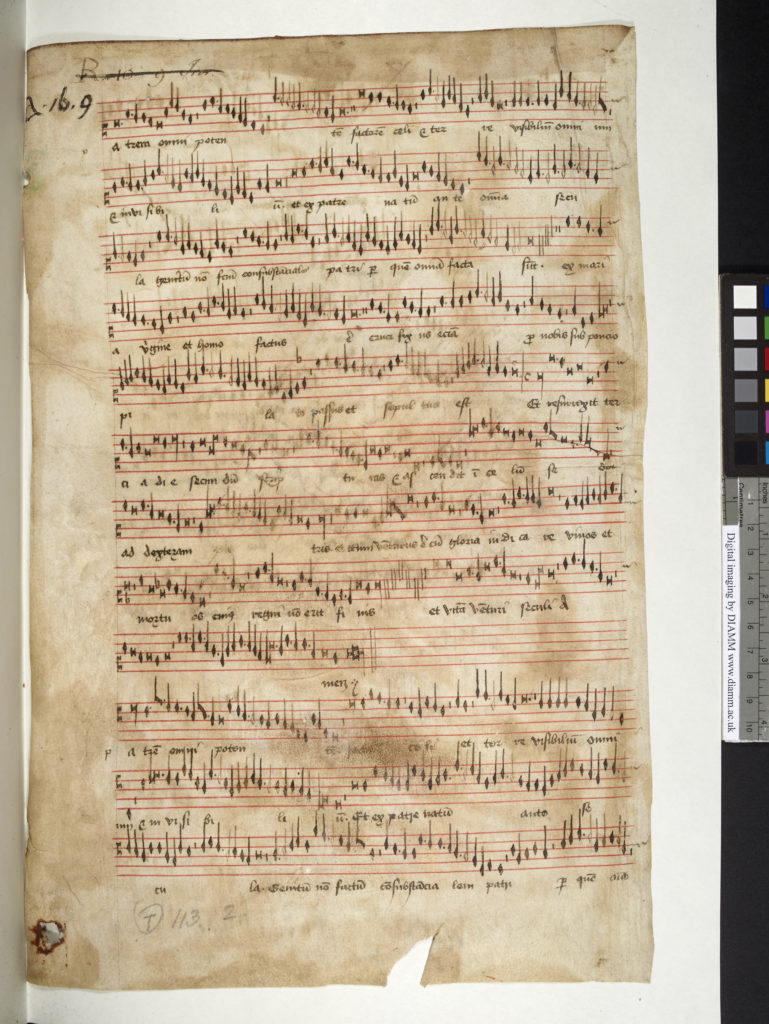

In the gallery below, you can see the original six leaves removed from Magdalen College MS Lat 100, which now form part of Worcester Cathedral Library MS. Add. 68. Photographs by Mr. Christopher Guy, Worcester Cathedral Archaeologist. Reproduced by permission of the Chapter of Worcester Cathedral (U.K.)

England, 1350s-1420s

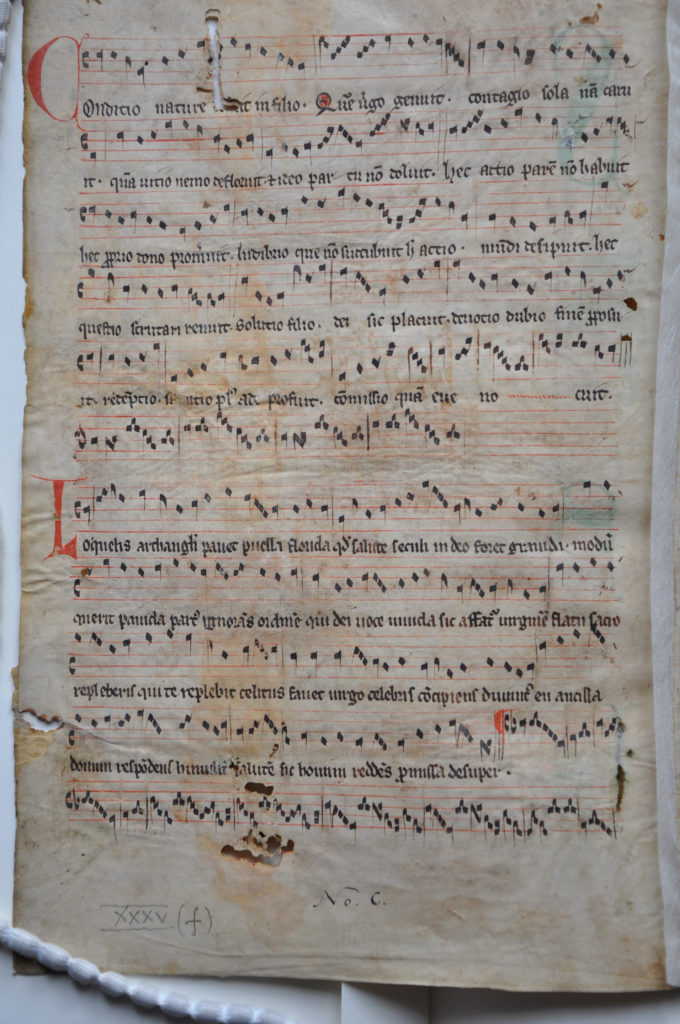

The gradual emergence of a more English style of polyphonic music is attested by two fragments coming from a music book, copied in the middle of the fourteenth century. To this period dates the three-voice Gloria in excelsis, here starting on pax hominibus, after the plainchant intonation which would have been sung by the priest. The original manuscript was still in use in the 1420s, when another composition–a motet–was added.

MS Lat. 266, f. 26; MS Lat. 268, f. 26

England, ca. 1420-1430

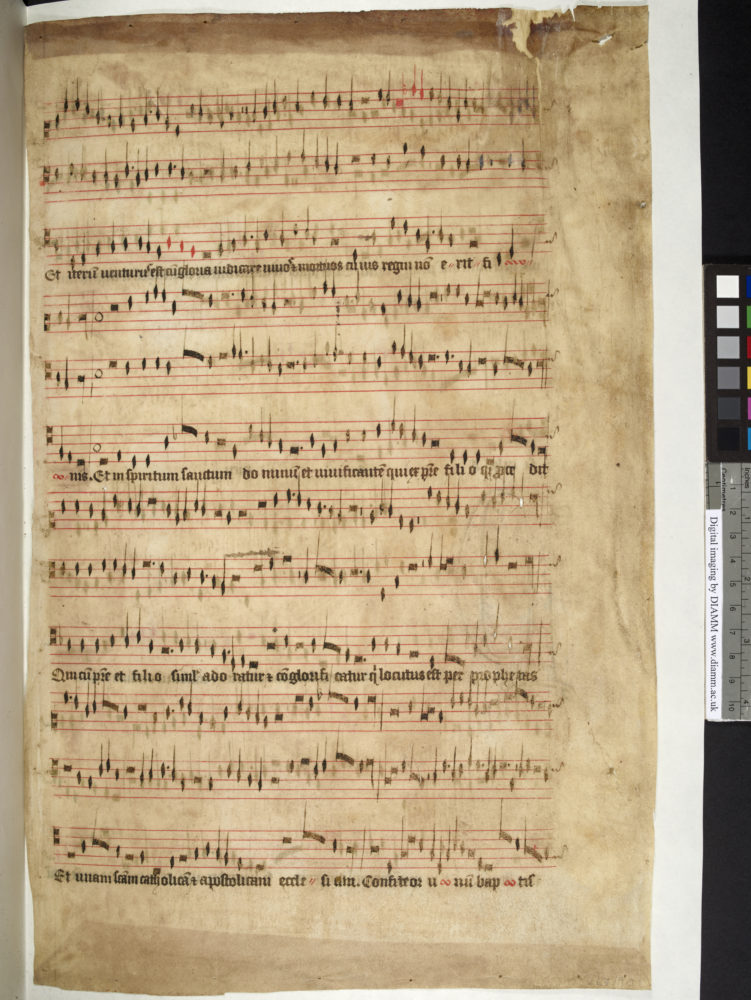

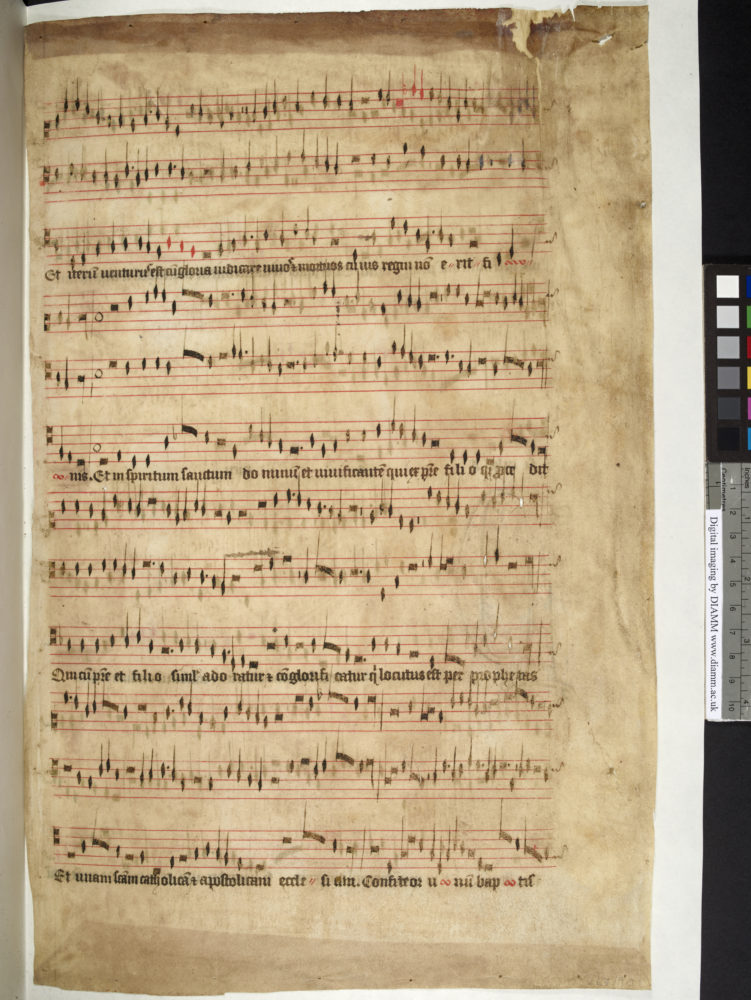

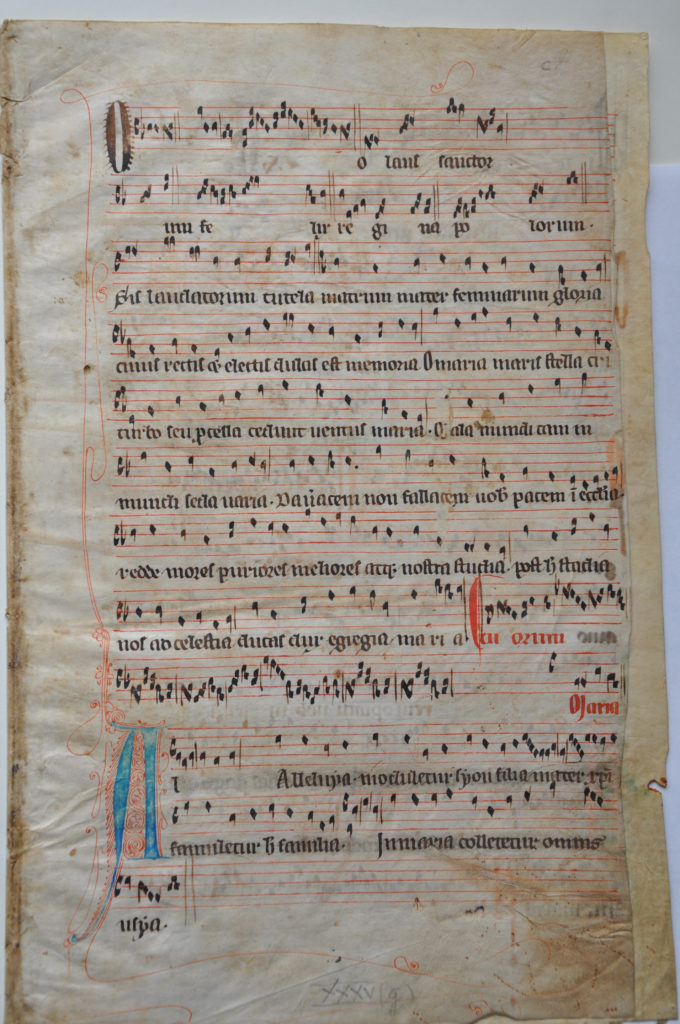

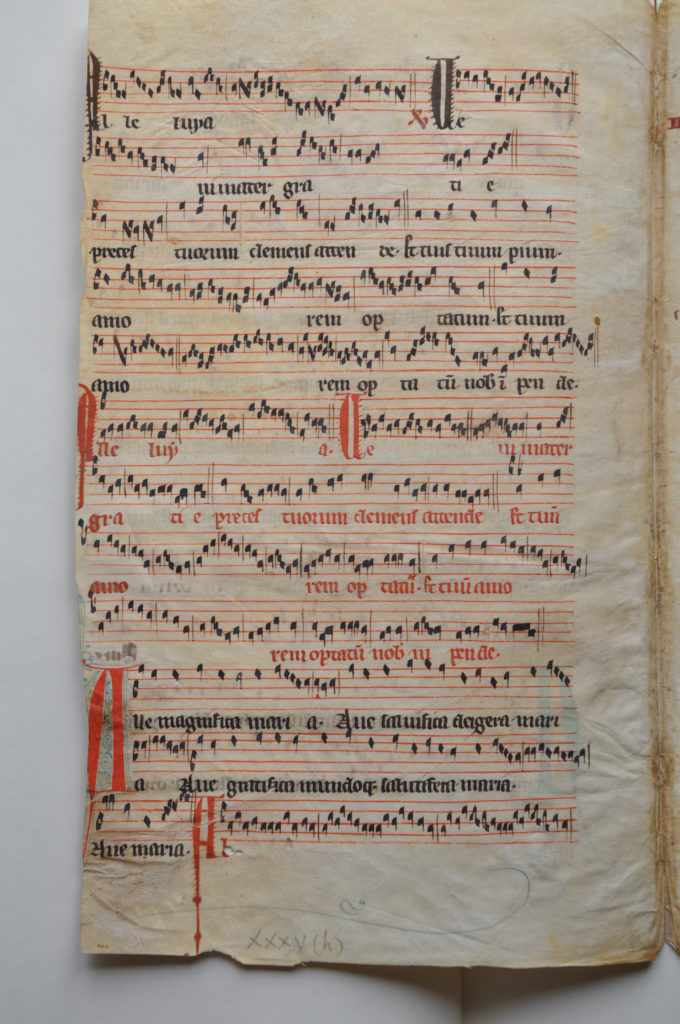

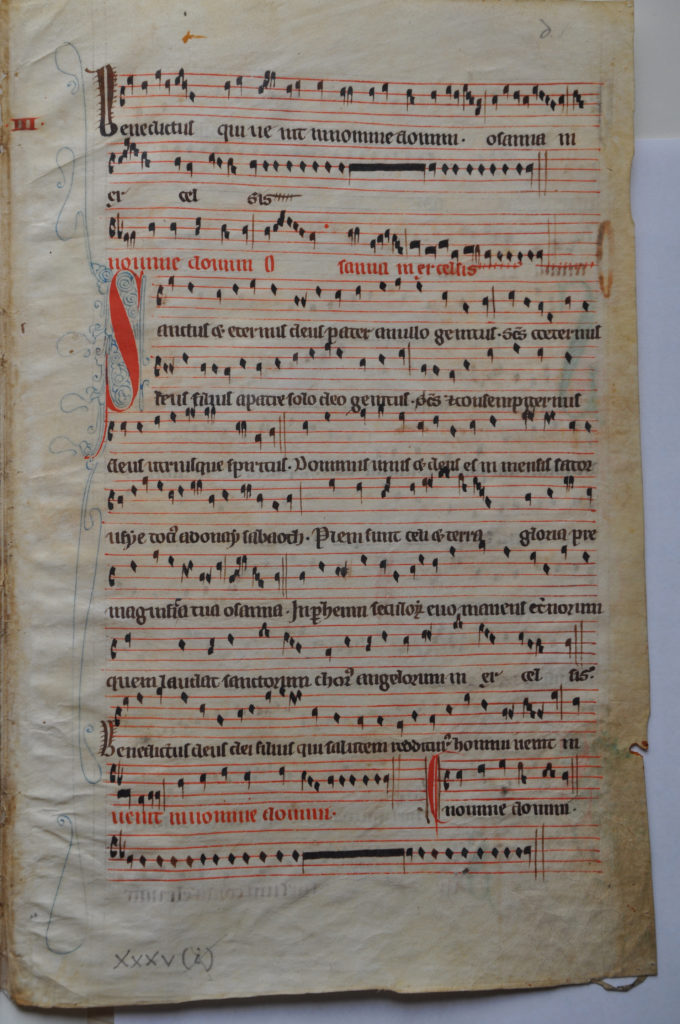

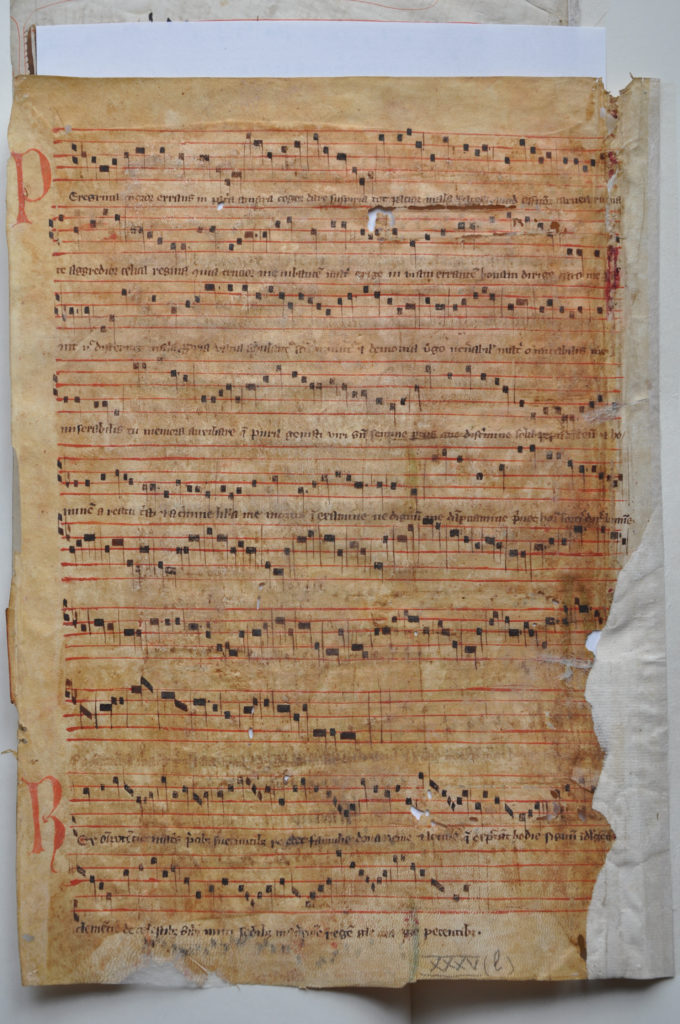

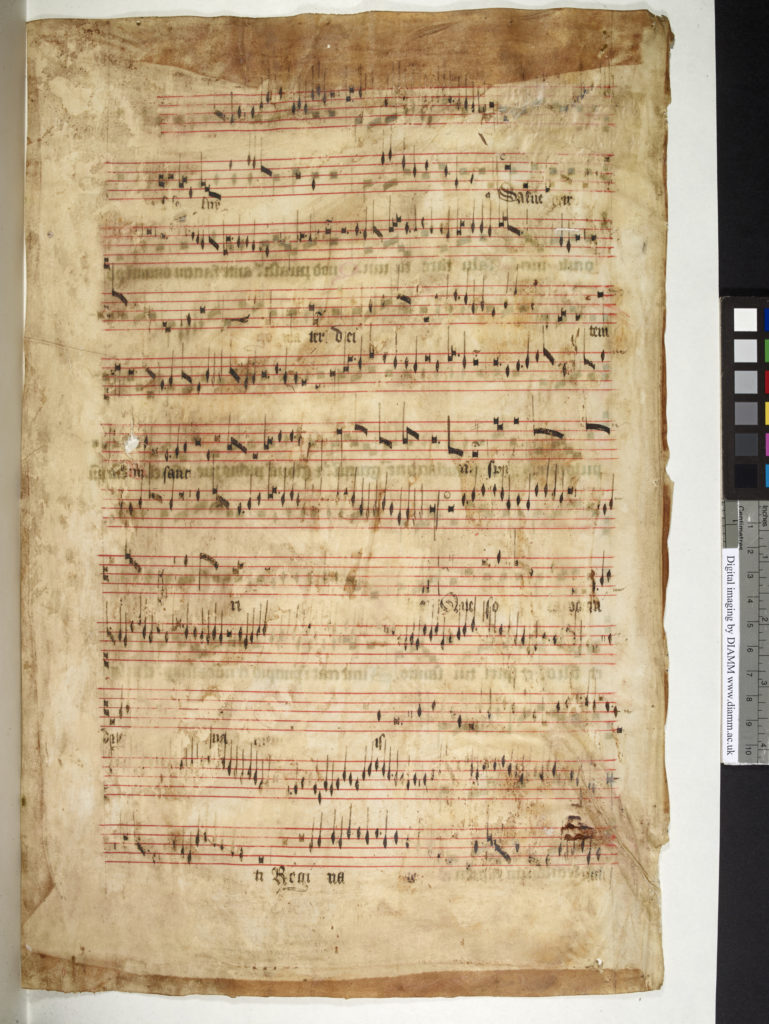

In addition to the famous ‘Old Hall‘ manuscript, the only surviving single volume of polyphonic music from late medieval England that has come down to us is preserved in another group of fragments, scattered in libraries and private collections across the world, four of which are still in Magdalen College Library.

These leaves came from a choirbook copied between 1420 and 1430, which was disassembled sometime in the early sixteenth century and used in a pair of Cambridge bindings by Nicholas Spierinck for a set of Roman and Canon Law printed in Lyon in 1499.

The intricacies of the extremely refined musical compositions, all liturgical settings, can be appreciated also by looking at the musical notation, where the variety of rhythmical solutions is reflected in the use of a wider range of different note values and their ‘coloration’ in red ink. It is possible that the choirbook was copied in an important musical institution in England at that time, such as the Chapel Royal of King Henry VI.

MS Lat. 267, ff. 89–92

The practice of recycling of parts of unused or discarded books was not limited to just medieval manuscripts. Earlier printed waste and later manuscript material on both parchment and paper are often found in bindings of early modern books. As the cost of new paper would amount to almost 70% of the capital investment in the making of a new book, binders kept up the tradition of using second hand parchment and paper to give their new books support. Old title deeds, sheets from receipt and account books, and proof sheets from printing presses are often found alongside medieval manuscript cuttings and fragments. Printed musical notation, again, is not an uncommon find in bindings as liturgical practices and musical notation and taste changed quite rapidly in the 16th century.

Fragments of lute music, probably English, c.1590-1600

Lute performances were at their apex of popularity in England in the last quarter of the 16th century and first quarter of the 17th century. These sheets were cut down from a practice book of hand-ruled paper which was likely twice the size of these now extant fragments and found in lining the binding of a later 17th century printed book. They contain six-line staves bearing French tablature for 6 and 7 course lute in ‘vieil ton’ tuning. Two of the fragments are clearly marked as ‘fantasias’, and one marked as being by ‘Alfonso’ – – The ‘Alphonso’ Fantasia can now be securely identified as the work of Alfonso Ferrabosco the Elder (1543-88). A keyboard concordance exists in GB-Lbl Add. MS 30485, f.43v-45v (‘A fancy Mr alfonso’). This, in turn, is an arrangement of a four-part consort piece for which a treble part survives in GB-Lbl Add. MS 32377, f.4, (‘fantasya 4 pts Alfonso’). [Credits Dr Lynda Sayce]

MS Lat. 265, ff. 61-62